Struggle and Triumph: The Legacy of George Washington Carver (NPS Movie 28min)

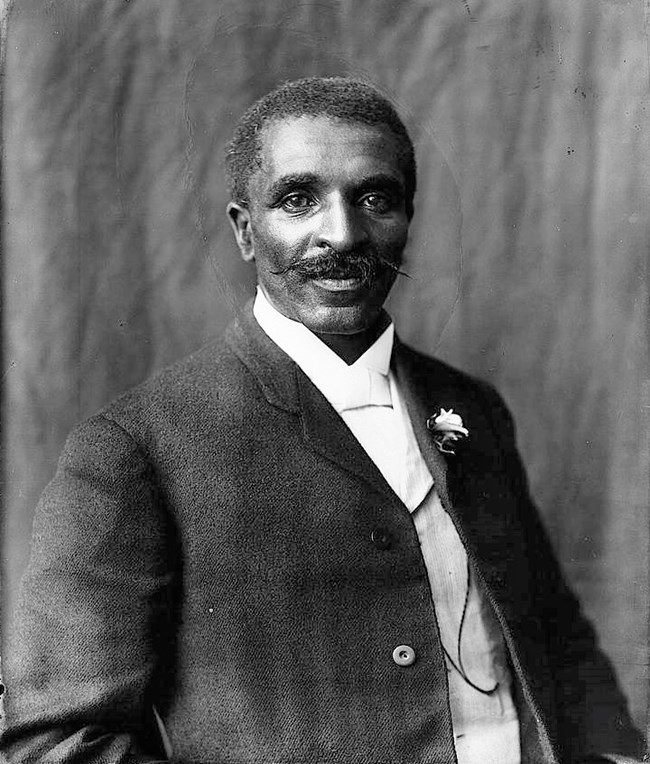

George Washington Carver

“The Primary idea in all my work was to help the farmer and fill the poor man’s empty dinner pail … My idea is to help the ‘man farthest down’; This is why I have made every process as simple as I could to put it within his reach.”

George W. Carver

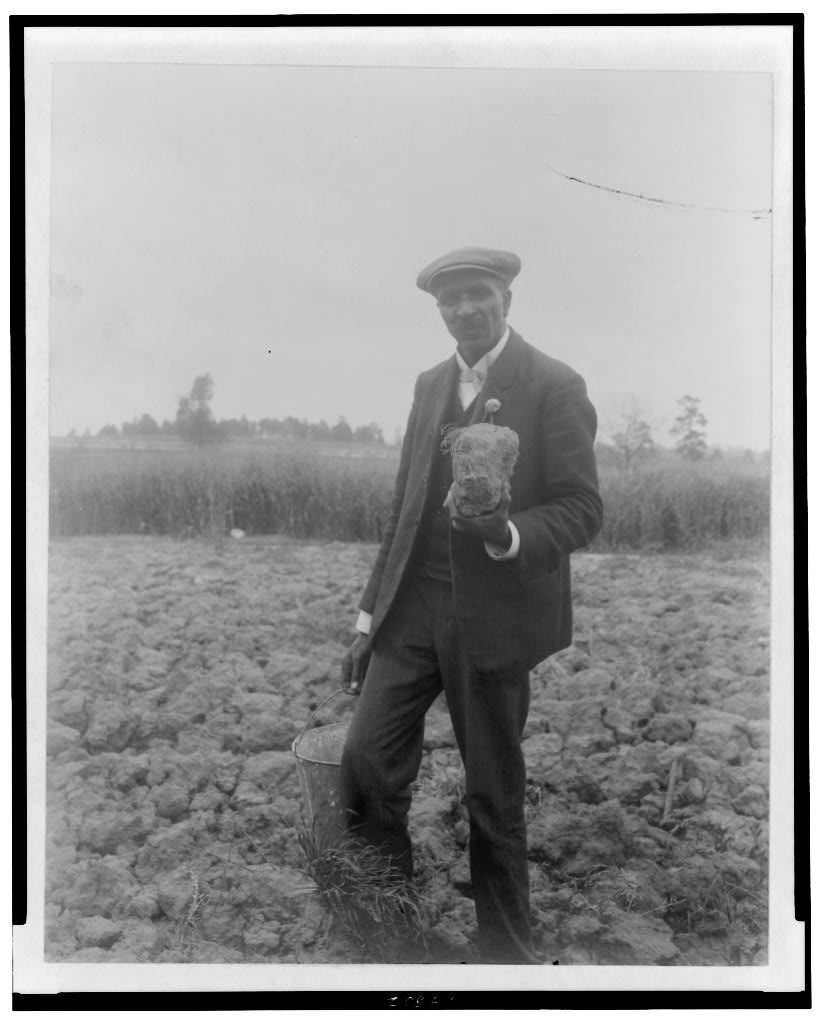

George Washington Carver, Born a slave around 1864, became a famous artist, teacher, scientist, and humanitarian. From childhood, he developed a remarkable understanding of the natural world. Carver devoted his life to improving agriculture and the economic conditions of African-Americans in the south.

In 1896, Booker T Washington hired Carver to teach agriculture at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Over a 40-year career, Carver taught many generations of Tuskegee students. He emphasized increasing the independence of local farmers. He believed that a practical education would both make African-Americans and white farmers self-sufficient.

“It has always been the one ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of my people possible and to this end I have been preparing myself for these many years, feeling as I do that this line of education is the key”

George W. Carver

The Early Years

“Day after day I spent in the woods… to collect my floral beauties… all sorts of vegetation seemed to thrive under my touch until I was styled the plant doctor, and plants from all over the county would be brought to me for treatment”

George Washington Carver

Born as a slave on a small farm in Diamond Grove, Missouri; the best information suggest he was born in 1864, near the end of the civil war. To appreciate nature and to assist his learning, George began a lifelong habit of taking long walks to observe nature and collect specimens.

Religion also played an important role in Carver’s life. It broke down social and racial barriers and was the inspiration for his research and teachings. Yet, he did not allow his beliefs to conflict with his scientific knowledge.

“The Great Creator… permit(s) me to speak to Him through… the animals, mineral and vegetable kingdoms…”

George Washington Carver

The School Days of G.W. Carver

“If you love it enough, anything will talk to you”

George Washington Carver

In the 1880s, local white schools did not allow African American students. Therefore, even though he had a great desire for knowledge, carver attended school whenever he could.

In 1890, Carver went to Simpson College Iowa to study art. Although African Americans were not allowed to register eventually Carver was admitted to class and he proved to be a talented artist. He paid for his tuition by doing laundry, cooking, and selling his paintings. Carver switched to agriculture studies because he saw this as a better way to contribute to his people. Carver set out to find practical ways to benefit African American farmers.

That led to enrolling at Iowa Agricultural College at Ames, Iowa. His teachers commented that Carver was “a brilliant student and collector.” He worked at the colleges’ experimental station until graduating with a Master of Science degree. He became an expert in field collecting, plant breeding, and plant diseases.

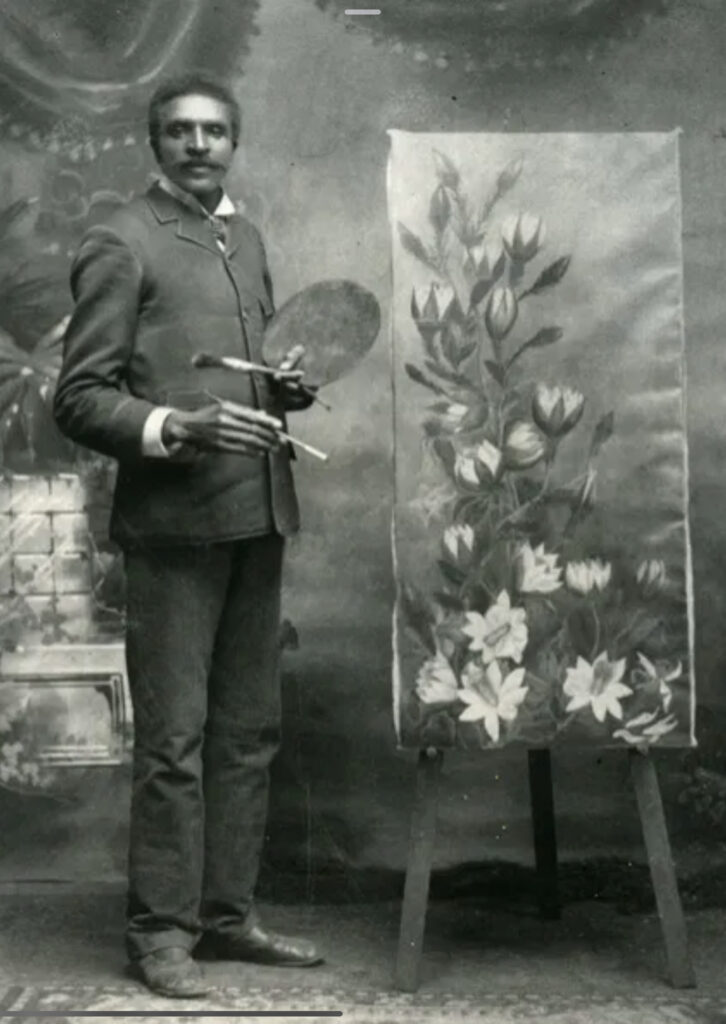

An Artistic Side

“When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world”

George Washington Carver

When young, Carver loved to draw and paint pictures. Originally an art student in college, he switched to agricultural studies. Yet, Carver continued to paint all of his life and one of his paintings won Honorable Mention at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Carver also would crochet, knit, and do needlework. Always practical, this enabled him to produce useful items for his friends. He learned how to dye his own thread and fibers with local trees, plants, and clay.

Carver collected local clays and extracted their pigments to make paints good enough to attract commercial paint companies. These paints were displayed in his laboratory and at county fairs. He used these paints in his artwork. He also developed house paint colors to encourage local farmers to improve the appearance of their homes. He arranged different paints into pleasing combinations for ceiling, cornices, and walls. Many buildings on the Tuskegee campus and throughout the area used these paint combinations.

Teaching Others

“Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom”

George Washington Carver

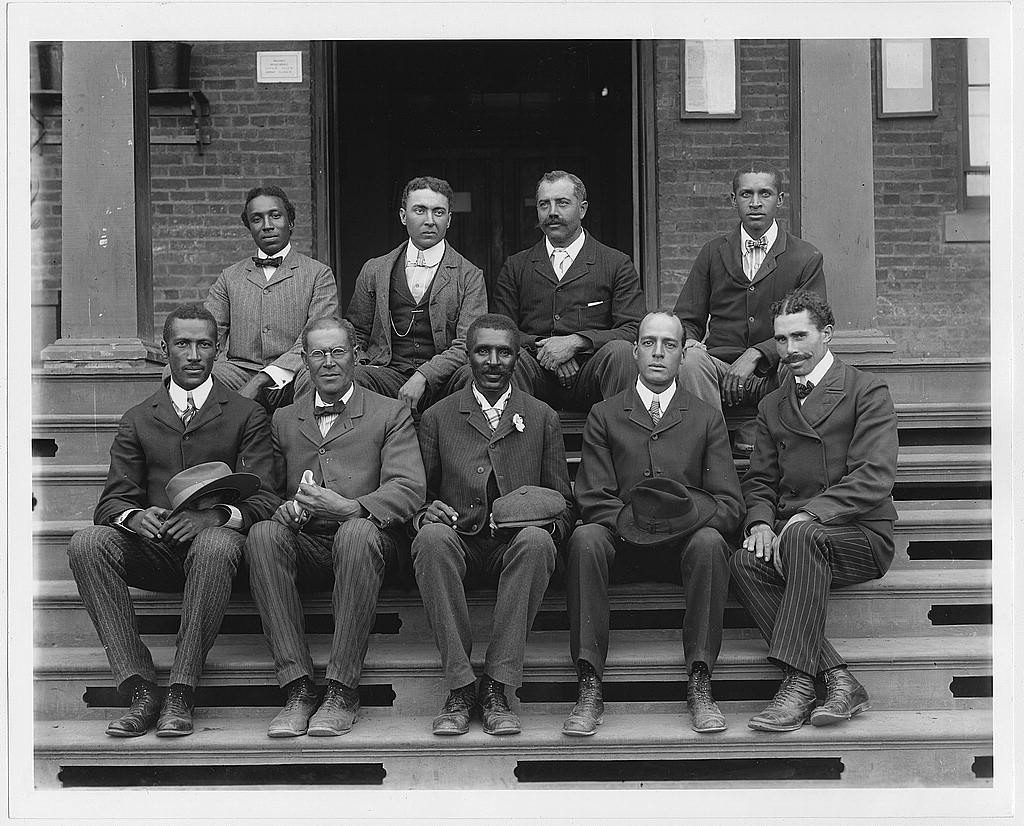

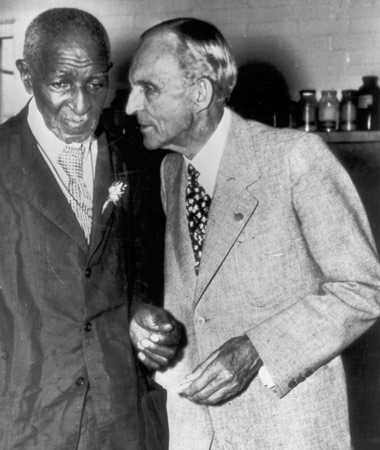

Booker T. Washington hired the best and brightest African American professionals to Tuskegee Institute. In 1896, he hired a young teaching assistant, George Washington Carver. They both believed a practical education was the best path to self-sufficiency for African Americans. Hired to head its Agriculture Department, Carver taught for 47 years, developing the department into a strong research center.

Carver spread the self-sufficiency message at schools, farms, and county fairs. Carver believed students learned best by doing. He expected students to “figure it out for themselves and to do all the common things uncommonly well.” Carver developed close personal relationships with his students, farmers, and powerful philanthropist with his engaging and charming talks and publications.

Booker T. Washington realized that Carver was a “great teacher, a great lecturer, and a great inspirer of young men and old men.”

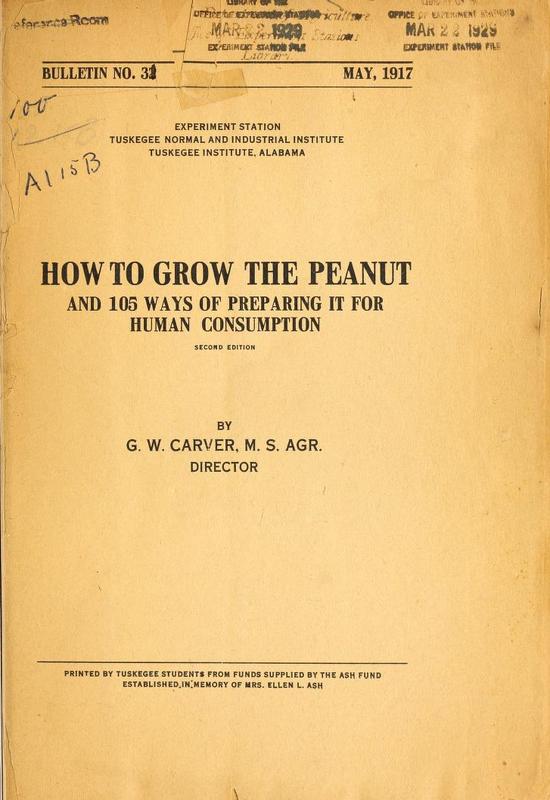

Useful Bulletins by G.W. Carver

“In painting, the artist attempt to produce pleasing effects through the proper blending of colors. The. Cook must blend her food in such a manner as to produce dishes which are attractive. Harmony in food is just as important as harmony in colors.”

George Washington Carver

Carver was a talented and innovative cook. He developed recipes for tasty and nutritious dishes that used local and easily-grown crops. He trained farmers to successfully rotate and cultivate new crops and encouraged better nutrition in the South. Carver developed an agricultural extension program for Alabama that used Tuskegee Institute bulletins. In these bulletins, Carver shared his recipes with farmers and housewives.

During his more than four decades at Tuskegee, Carver published 44 practical bulletins for farmers. His first bulletin in 1898 was on feeding acorns to farm animals. His final bulletin in 1943 was about the peanut. Other individual bulletins dealt with sweet potatoes, cotton, cowpeas, alfalfa, wild plums, tomatoes, ornamental plants, corn, poultry, dairying, hogs, preserving meats in hot weather, and nature study in schools.

His most popular bulletin, How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption, was first published in 1916 and was reprinted many times. Carver’s bulletins were not the first American agricultural bulletins devoted to peanuts, but his bulletins were more popular and widespread than others.

Agricultural School On Wheels

Booker T Washington directed his faculty to “take their teaching into the community”

To take lessons to the community, Carver designed a “movable school.” Students built a wagon named for Morris k Jesup, a New York financier who gave Carver the money to equip and operate the movable school. The first one was a horse-drawn agricultural wagon called a Jesup Wagon. Later, a truck still called a Jesup Wagon carried agricultural exhibits to county fairs and community gatherings.

By 1930, the “Booker T Washington Agricultural School on Wheels” carried a nurse, a home demonstration agent, an agricultural agent, and an architect to share the latest techniques with rural people. Eventually, educational films and lectures were presented at local churches and schools. These vehicles were the foundation of Tuskegee’s extension services.

Research For Practical Applications

“Soil enrichment, natural fertilizer use, and crop rotation” were Carvers message to students and farmers

From 1915 to 1923, Carver developed techniques to improve soils depleted by repeated planting of cotton. Also, in the early 20th century, the boll weevil destroyed much of the cotton crops, and planters and farm workers suffered. Together with other agricultural experts, he urged farmers to restore nitrogen to their soils by practicing systematic crop rotation: alternating cotton crops with the planting of sweet potatoes, peanuts, or soybeans. These alternative crops restored nitrogen to the soil and were also good for human consumption. Following the crop rotation practice resulted in improved cotton yield and gave farmers alternative cash crops. He also began research into crop products (chemurgy), and taught generations of black students farming techniques for self-sufficiency. In these years, he became one of the most well-known African Americans of his time.

Always looking for practical solutions from his wide-ranging research, Carver experimented with seeds, soils, soil enrichment, and feed grains. All of his efforts were geared to increasing the self-sufficiency of African American farmers. Ahead of his time, Carver used plant hybridization and recycling the use of locally available technology.

Carver’s research also looked to provide a replacement for commercial products, which were generally beyond the budget of the small one-horse farmer. George W. Carver reputedly discovered three hundred uses for peanuts and hundreds more for soybean, pecans, and sweet potatoes. These alternative products included adhesives, axel grease, bleach, buttermilk, chili sauce, fuel briquettes, ink, instant coffee, linoleum, mayonnaise, meat tenderizer, metal polish, paper, plastic, pavement, shaving cream, shoe polish, synthetic rubber, talcum powder, and wood stain.

Later Years

“Professor Carvers Advice” – George W Carver’s syndicated newspaper column

During the last two decades of his life, Carver seemed to enjoy his celebrity status. He was often on the road promoting the Tuskegee Institute, peanut, and racial harmony. Although he only published six agricultural bulletins in 1922, he published articles in peanut industry journals and wrote a syndicated newspaper column., “Professor Carver’s Advice.” Business leaders came to seek his help, and he often responded with free advice.

From 1933 to 1935, Carver worked to develop peanut oil massages to treat polio. Ultimately researchers found the massages, not the peanut oil, provided the benefits of maintaining some mobility in paralyzed limbs.

Carver had been frugal in his life, and in his 70s, he established a legacy by creating a museum on his work and the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee to continue agricultural research. He donated $60,000 in his savings to create the foundation.

G.W. Carver Last Days

Inscribed on Mr. Carver’s tombstone are the words, “He could have added fortune to his fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world”

Upon returning home one day, Carver took a bad fall down a flight of stairs; he was found unconscious by a maid who took him to the hospital. Carver died January 5, 1943, at the age of 78 from complications (anemia) resulting from his fall. He was buried next to Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute.

National Recognition and Naming

His work, which began for the sake of the poorest farmers, paved the way for a better life for the entire South and became an inspiration to all.

George Washington Carver was born a slave. Since his owner was Moses Carver and given the first name of George, Carver referred to himself as Carver’s George. This was more a property description than a name. When George left to attend school, he slept in a barn owned by the Watkins family. Of hearing how George referred to himself, Mrs. Watkins told him that was no proper name and declared that henceforth he would be George Carver.

Like the man, Carver High school did not start with that name. The Phoenix Union High School district opted to officially embrace segregation. In 1925, to accommodate African American high school students, a bond issue was passed to erect a new high school building. The new school was named the Phoenix Union Colored High school until 1940 when the school became the Phoenix Colored High School. On January 5, 1943, George Washington Carver Died and a few months later the school took on the name of this distinguished educator, scientist, and innovator. In 1953, educational segregation was ruled unconstitutional in Arizona and the school closed the following year.

Why are so many schools, parks, and other landmarks named in honor of Carver? Carver came to stand as a symbol of the intellectual achievements of African Americans. He brought about a significant advance in agricultural training in an era when agriculture was the largest single occupation of Americans. It is so often said that Carver saved Southern agriculture and helped feed the country. His great desire was simply to serve humanity; and his work, which began for the sake of the poorest black sharecroppers, pave the way for a better life for the entire South and became an inspiration to all.

GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER NATIONAL MONUMENT

George Washington Carver National Monument orientation video. (NPS Movie 5min)

Our Monument to George Washington Carver

“How far you go in life depends on you being tender with the young, compassionate with the aged, sympathetic with the striving and tolerant of the weak and strong. Because someday in your life you will have been all of these.”

George Washington Carver

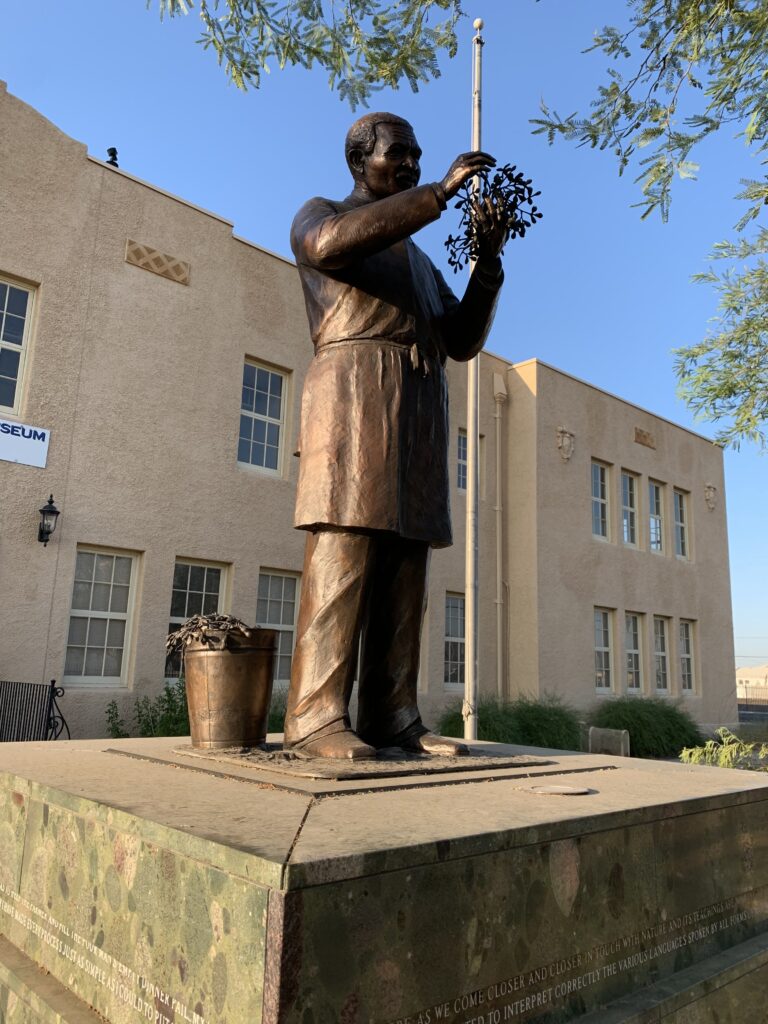

The George Washington Carver statue greeting visitors to the Carver Museum is an exhibit all to itself. The sculpture, Mr. Ed Dwight, is an internationally acclaimed sculptor whose works grace various venues around the United States. Among his works are major African American historic figures.

The Carver Statue was unveiled on February 15, 2004, in a ceremony where Governor Janet Napolitano, among many others, addressed the crowd. The artist, Ed Dwight, spoke movingly before the unveiling. There were musical presentations and acknowledgments of many distinguished guests. Visitors who have viewed and photographed the statue have praised its artistry.

The Carver Statue is an artistic achievement and a worthy monument to its namesake. This exquisite work faithfully captures Carver’s delicate features and somehow reflects the genius and hope that defined the man.